Interview with Charbel-joseph H. Boutros en Stéphanie Saadé. By Valentijn Byvanck, januari 2021.

Valentijn

Dear Stéphanie and Charbel: We started talking about the home as a theme for this exhibition before corona hit, before Stéphanie knew she was pregnant and before you were blasted out of your apartment in Beirut. Already at the time, the theme seemed logical to me, perhaps because of the nomadic nature of your existence, or perhaps because I thought it was suitable because it was something that brought you and your diverging practices together. Stéphanie was already working on the now very topical works Building a Home with Time and We’ve Been Swallowed by Our Houses. How do you yourselves see the connection between the theme and the development of this project?

Stephanie

Dear Valentijn, my feeling is that things are changing so fast nowadays that artworks should be dated not only by year but also month, day, even hour … what we have witnessed since March 2020 in the world, and since October 17, 2019 (and definitely even before) in Lebanon, are changes of great importance. We have been more surprised and more often surprised than ever, and it keeps going on. The first work you mention, Building a Home with Time was indeed conceived in 2019, so before all the changes that you mention occurred. The work refers to my childhood, the part of my life that I shared with my country’s tormented history. And I naively assumed that conflict and violence were part of my past. But while I was working on it, we went through a popular uprising, the Lebanese pound’s devaluation, hyperinflation, a global pandemic and a deadly blast … to cite a few … and this past suddenly came back to the surface, taking the color of more vivid events. Building a Home with Time evoked the slow action of building a place of your own, of building your own self probably, inscribed in time, but also building on ruins, on a difficult terrain, and not necessarily a flat one. Maybe it’s not a coincidence that I called the work “Building …” in the present participle, as if this process was to be ever ongoing.

The second work you mention We’ve Been Swallowed by Our Houses is dated from 2020 and the idea of it came during the first lockdown in Beirut. We were still in our home, which also contained our studios. The lockdown gave me the feeling of a thickened indoor space, one that would have swallowed you and that wouldn’t spit you out anytime soon! I was pregnant and was experiencing the beautiful feeling of a confinement within my body, in the coziest and most wonderful way. In addition, I felt the confinement provided a much needed break from life’s crazy rhythm. Soon after, however, it also led to a suffocating feeling. Today, home is the place in which and from which I’m waiting to be spat out, even, why not, vomited out; not by the house, as this physical space has changed already three times for us since the beginning of the pandemic, but by the home.

I link what’s happening to us to biblical stories such as Jonah and the whale, or, in a more modern form, the tale of Pinocchio. It’s interesting to note that, to illustrate the story, Jonah is either pictured as being swallowed by the whale, or being spat out. I guess it’s a question of perspective, of seeing the glass half empty or half full. In the tale of Pinocchio, there’s an active attempt to exit, which I find interesting. Today, we are somehow more and more passively waiting for the doors to open again, and the pandemic and our realization of what it actually is and what it actually means and does, is eating out all that’s left of our disobedience, rebellion, and other feelings of the sort. We’re somehow starting to become afraid of exiting the comfort of our jails. For safety, protection, and survival purposes we have to stay passive. Passivity is our only weapon, it’s the only way to fight. The idea of the show came to us before “home” became a new concept, but it also evolved while this process was ongoing. We felt it was still valid to explore it, no matter what it would become at the time of our exhibition.

We’re somehow starting to become afraid of exiting the comfort of our jails. For safety, protection, and survival purposes we have to stay passive. Passivity is our only weapon, it’s the only way to fight.

Charbel

With the pandemic, home became a sort of refuge from a hostile outside; the only safe place on earth becomes one’s own home. Of course, home already played this safety role even before the pandemic started. But the outside didn’t wear this dramatic character of hostility, like it does now. The outside used to evoke escape, the future, holidays, the encounter with others, the horizon, friendships. All of this vanished, which is why we find ourselves confined and hiding in our homes, waiting for better days to come. It is a sort of prehistoric scheme that we are experiencing today. Home becomes again the protective cave, a shelter from the outside wilderness and beasts. That said, the exhibition Intimate Geographies presents not a direct reaction to the pandemic. We seek to create works and exhibitions that transcend specific contemporary situations or trends.

Valentijn

In our conversations you have voiced the ambition to make Marres a home for your art. Even though we know many art works we see in museums have originally been produced for the home, we have become accustomed to thinking that the museum is the proper home for art. I am very curious to see in this exhibition what the home will bring to the art, and art to the home. Will your artworks be more at home in the home of Marres?

Charbel

Our aim here was to create an uncanny situation, where visitors would wonder if they are in an exhibition or in a home. We intended to blur this limit and came up with the idea of having two protagonists inhabiting the exhibition. The protagonists form a couple of two artists. They are not our alter egos, but of course they are modeled on our experiences and speak our dialogues. They live in the house that also contains their working spaces. They are preparing an important exhibition and hence receive phone calls from their gallerists, the people that they work with (assistants, craftspeople), as well as visits by, for instance, you as the director of the art institution where the show will take place. The visitors could easily mistake the artists for other visitors. Yet, the awkwardness of their actions, and their behavior makes their presence more salient. What are they doing there? What is the purpose of the enigmatic rituals — from phone calls to naps — that they perform? The visitors gradually understand that they have entered a home. Yet, they will also be a little befuddled by the entanglement of furniture, artworks, and actors. The piece about the mausoleum of a gallerist opens further questions such as the complex agency of the art world, and the making of art. This is important to us: that we question the typology of the exhibition within a precarious and fragile art world.

Stephanie

It is true that a lot of what we consider as art objects today that we admire in museums, was initially made for homes. What is interesting is that functional objects, made for homes, once also held magical and spiritual qualities. The plate, the bowl, and the spoon were potentially efficient and powerful talismans, connecting humans to something greater. This was lost when the objects landed in museums: since their magical qualities are no longer tangible to us they give us the disturbing feeling that we’re looking at “dead” artifacts. In my work, I often use mundane objects or ‘situations’ which I divert toward a transcendence. I like to reenchant these day-to-day items in order to make them meaningful again, potentially useful in other contexts than their original ones. Intimate Geographies presents several artworks that depart from objects that belong to a domestic setting and vocabulary. Paradoxically, the mundane objects, reinstilled with new properties, are again redefined by the new situation they find themselves in: in a house among furniture, maybe even used by a couple … it’s confusing. We could answer your question “is art more at home at home?” by saying: let’s see what the home is today and whether it has something to offer to art.

Our aim here was to create an uncanny situation, where visitors would wonder if they are in an exhibition or in a home. We intended to blur this limit and came up with the idea of having two protagonists inhabiting the exhibition.

Valentijn

The relationship between time and memory is a recurrent theme in your work. Could you tell me why this is so important?

Stéphanie

I’ve always been interested in a playful approach of time rather than the traditional dramatic linear one. My works are meant to provide the possibility of bringing back elements of the past and weaving them into the present. Memories and objects deserve to be looked at again and have their lives prolonged. New facets of them appear, fresh ones that are yet to be covered by time’s patina. Safeguarding these isolated elements gave me a feeling of satisfaction after the August 4 blast in Beirut, and the ensuing exodus of which we were part. It’s not that all our belongings were destroyed, properly speaking, but I would say more a part of ourselves. My works are like dysfunctional, or enhanced Proustian madeleines … they project you into the past, not my past in the end of the day, more each one’s own past, or even imaginary pasts, but they project the object into a greater future. In that they become “legendary,” or favorable, or welcoming to the creation of each viewer’s personal legend.

Charbel

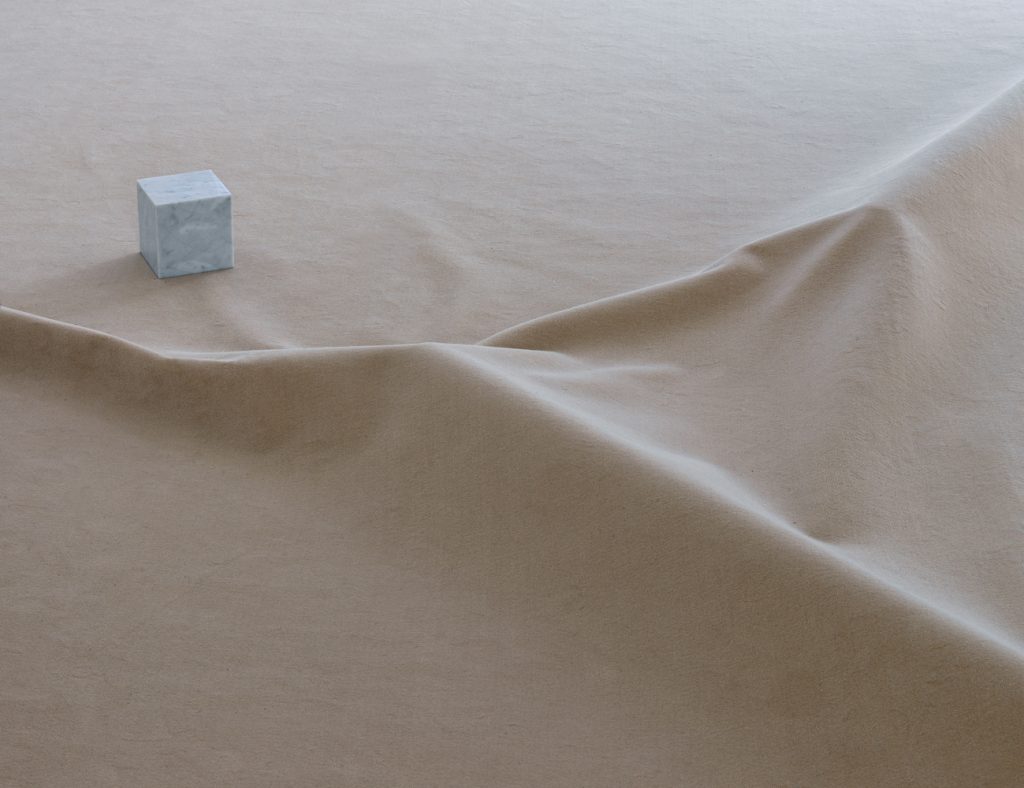

I am interested in what I qualify as charged abstraction: an abstraction that is not due to the energy of colors and the rhythms of the composition per se, but an abstraction that is defined by the invisible charge that it endured, like a material that is heated, or a human that received a charge of emotions after having an experience. This invisible charge is an important component in my practice. This is how I proceed with my installations, sculptures, or performances: I take a material which could be the sun, a video, marble, the night, or a shoe and I charge it with a unique experience. This experience can be intimate or more universal. You can see that in my work Spring, a work that could formally refer to early abstraction, but which is in reality a paper charged-exposed to the sun of spring, to all the suns that spring has witnessed. It’s an abstraction made of a season. In Geography and Abstraction we see a wavy abstract shape, undulating: a carpet. But this new geography is a portrait of a man, a portrait of an institution, and this man is the director and curator of the institution. It is his body that is represented here by three concrete tubes hidden under the carpet, creating folds and a new landscape that the visitor will cross or lie on. Here the intimate body becomes a conceptual plinth on which the visitor will walk. The intimate is woven with something more linked to the functioning and representation of an institution. This is something very typical in my practice, to proceed by a telescopy of scale and narratives. The intimate meets the universal and vice versa.

Related exhibition

Read more about the duo exhibition Intimate Geographies by Charbel-joseph H. Boutros and Stéphanie Saadé.